PhD Research

The work documented below forms part of Sue Goldschmidt’s Doctoral Viva submission.

In the House of Ephra and Bahmanduch

Flock, 2021, Private house, Photo: Nedim Nazerali

Sue is a PhD researcher at Westminster University’s Centre for Research and Education in Arts and Media (CREAM). Her practice-based research is titled “Aramaic Incantation Bowls and Contemporary Ceramic Art Practice”. It investigates connections between historical ceramic objects, critical theory and contemporary ceramic art practice, through the study of Aramaic incantation bowls from 5th-7th century CE Iraq. Through interdisciplinary critical and creative approaches, the research establishes connections between the fields of contemporary ceramic art practice, archaeology, ancient history and critical theory. The Aramaic bowls are ceramic bowls made from ordinary buff coloured clay covered in magical texts from 5th -7th century Iraq, found buried upside down in the floors and courtyards of ordinary Babylonian homes. Fundamentally concerned with the protection of occupants and the banishment of demons, they invoke a plethora of supernatural beings from across cultures to assist in this endeavour.

Research centres on a close reconsideration of these texts and the production of ceramic art work comprising an installation of three rooms, a spatial triptych in which the decorative fabric of the home manifests the physical and psychological unease registered in the bowl texts. This approach references the quasi-religious nature of the magic bowls, as well as the domestic environments in which they were usually found, and draws on the bowl texts as an archive of partially told stories with emergent themes and narratives. Types of spells include those for curative healing, protection of unborn or young babies, love, problems affecting marriage, financial wellbeing, protection against malicious magic, and, rarely, aggressive curse texts.

In the House of Ephra and Bahmanduch invites viewers to experience a triptych of three spaces, each cloistering one of three ceramic installations: Sub Rosa, Lilith by the Red Sea Carpet and Flock. These immersive room-scapes re-imagine Babylonian domestic interiors in which the bowls were typically unearthed, manifesting the psycho-space of the homes in which magic bowl praxis was evident. The bowls’ common use occurred in a culture that embraced the idea that garments and buildings could take on human sickness, and afforded language and voice real efficacious power. In the House of Ephra and Bahmanduch explores the idea that the bowl texts buried in the floor, and probably spoken into the air, together with the emotions and thoughts that brought them forth, permeate the space, and become embodied within the decorative fabric of the space. Home becomes a personification which manifests the psychology and metaphysical thinking of its occupants, a Wordsworthian or Brontëan material pathetic fallacy of interior spaces, expressed through material mimicry.

In the House of Ephra and Bahmanduch unites the three installations in a triptych of spaces, each relating specifically to walls, floor or ceiling, the main elements of a room. The triptych’s title derives from Montgomery bowls AIT 1 and 13, which were written for Ephra bar Saborduch and Bahmanduch bat Sama, and unearthed at Nippur by the University of Pennsylvania Expedition between 1888 and 1889 (Montgomery, 1913). The first text is written for Ephra to protect him against lilith demons that are causing serious disturbance in his and Bahmanduch’s home. The text describes a long list of dreadful things the liliths are capable of doing, including, terrifyingly, the ability to ‘trample and scourge and mutilate and break and confuse and hobble and dissolve (the body) like water’. They ‘appear to mankind, to men in the likeness of women and to women in the likeness of men, and with mankind they lie by night and by day’ (Montgomery: 118). The second text, written for Bahmanduch, is both a love amulet and a charm against barrenness. Together these texts encapsulate many of the ideas that preoccupy and perplex this engagement with the Aramaic bowls. Triptychs were portable (protective) altar pieces, and the use of the triptych form in its monumental incarnation here foregrounds the quasi-religious nature of the objects under investigation. By presenting this work as a triptych it assumes theological importance, in which liminal objects buried underground, first in the dirt floors of Babylonian homes, now in the basements of museums, take centre stage. The triptych structure enables the unknowable material Nippur house to find a form, whilst at the same time emphasising the quasi-religious nature of the Aramaic bowl texts and praxis.

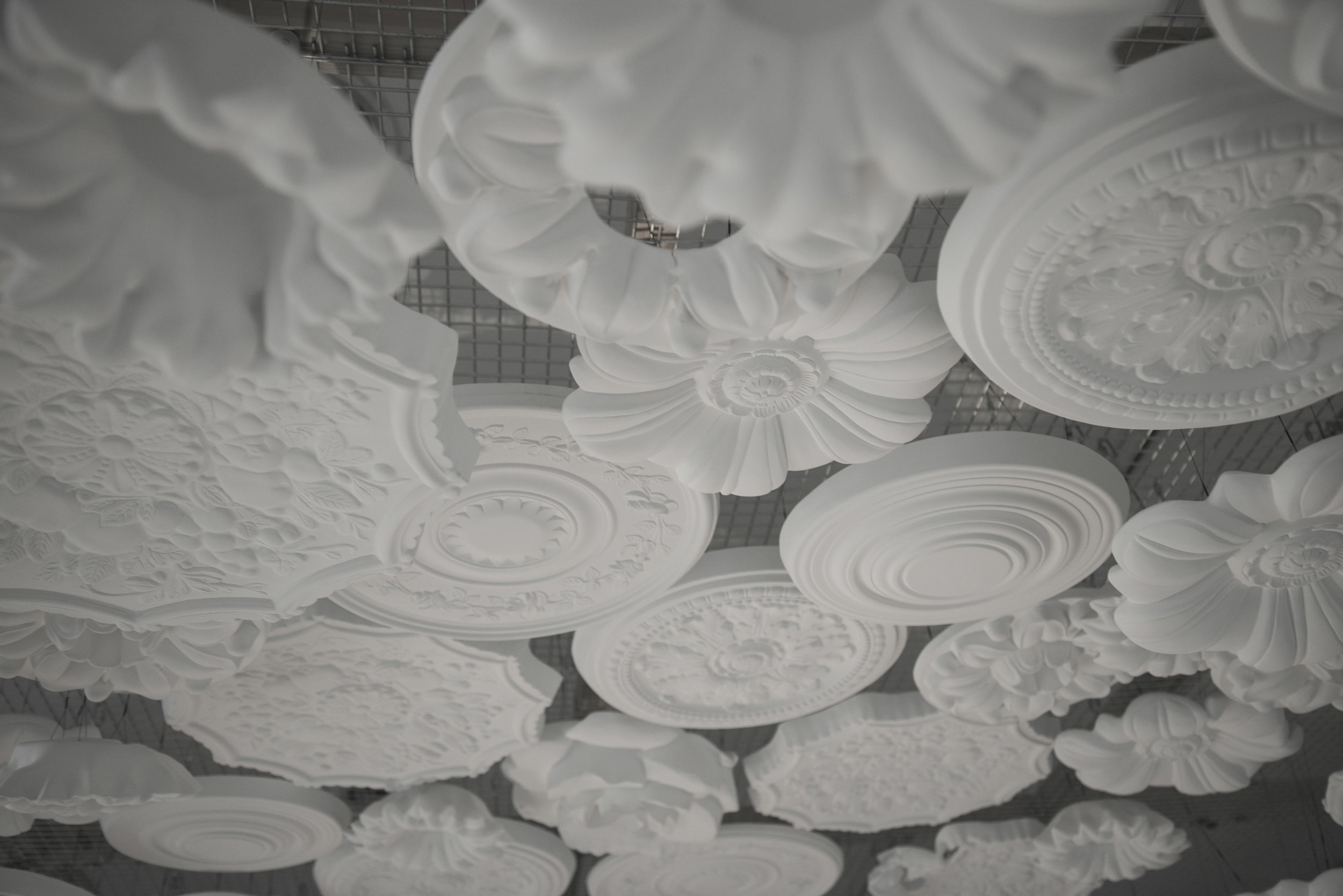

Sub Rosa

Sub Rosa, July 2017, London Gallery West, Photo: Nedim Nazerali

Photos 1-5 and video clip: Nedim Nazerali

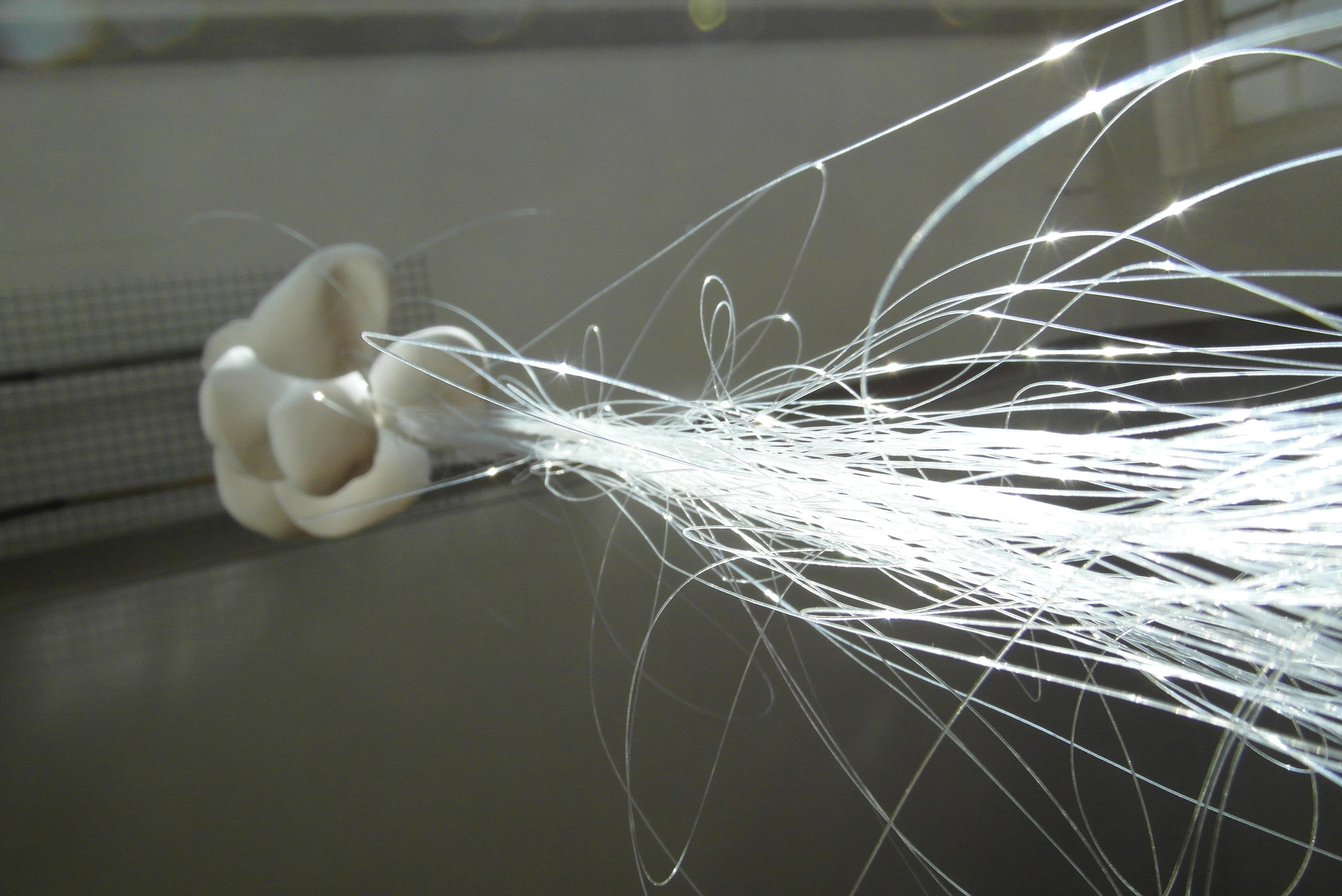

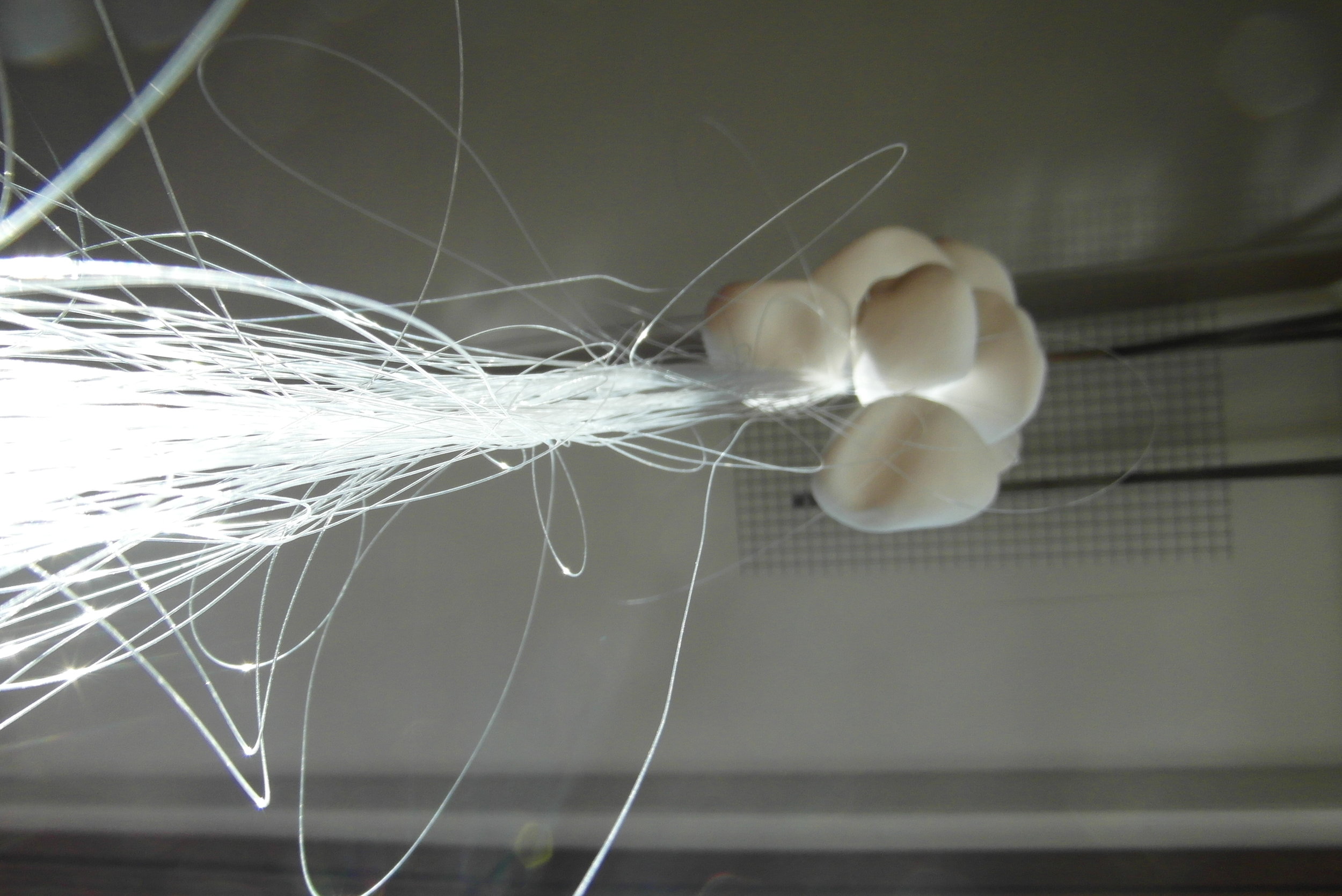

Sub Rosa is a large circular ceiling piece comprising seventy five bone china ceiling roses approximately three meters in diameter. These hang suspended above the viewer in a dome shaped spiral formation, echoing the upside down placement of Aramaic bowls. As the ceiling roses circle outwards, cracks and distortions appear, registering trauma and disturbance, creating a bowl formation that begins to come unraveled. Sub Rosa’s circular form delineates a space for viewers to physically enter, one in which they find themselves central to a work suspended precariously above their heads. Installed in an intimate space, viewers beneath Sub Rosa feel the trace of an invisible wall encircling and enclosing them, setting up a dialectic between inside and outside space. Sub Rosa’s title alludes to the physical and emotional position of both Aramaic bowl clients and contemporary viewers of the work: The title of the work draws the viewer beneath it, the circular form delineating a space for the viewer to enter and become literally and experientially ‘sub rosa’.

Plasterwork ceilings have a long association with notions of secrecy beginning as far back as the Ancient Greek myth of Eros, who gave a rose to Harpocrates, the God of silence, as a bribe to prevent any unpleasant revelations about the behavior of Cupid’s mother Venus. The white rose came to symbolize secrecy and silence, and during Roman times it became customary to paint or suspend a rose in the ceiling above a meeting table. Roses were painted on the ceilings of these rooms: Nothing said “sub rosa” was to be repeated elsewhere. The condition of being ‘sub rosa’ seems to have affected a number of Aramaic bowl clients, with texts written to make someone fall in love with a specific person, or compel an errant husband to leave ‘Lilith’ and return to his wife. In a curious linguistic coincidence, Bowl texts refer to themselves by the word raz, translated as “secret”, “mystery” or “spell”, the Aramaic word audibly close to the English word “rose”.

Lilith by the Red Sea Carpet

Lilith by the Red Sea Carpet, March 2019, Ambika P3, Photo: Sylvain Deleu

Photos 1-3, 5-6: Sylvain Deleu

Lilith by the Red Sea Carpet is an indoor carpet-garden made of unfired Ming porcelain exploring disquieting narratives surrounding Lilith. Arguably the most prominent demon mentioned in the bowl texts, her evocative tale holds centre stage in the magical thinking surrounding the bowls, and here in Lilith by the Red Sea Carpet. A descendent of the lilitu in ancient Mesopotamian cuneiform texts, Lilith is mentioned in Jewish folkloric and mystical texts such as the Alphabet of Ben Sira (c. 700-1000 CE) and the Zohar as well as in Isaiah 34:14. Lilith mythology identifies her as Old Testament Adam’s first wife, banished from the Garden of Eden because of her disobedience to him, to live on the shores of the Red Sea (a probable mistranslation from the Biblical Hebrew ‘Sea of Reeds’). Lilith survives into medieval Jewish folklore, evolving into a siren-like seductress, a dangerous embodiment of dark feminine powers. Able to enter the physical world through mirrors, she returns from isolation to take up residence in cellars and attics of human homes, establishing parallel families through adulterous relationships, and wreaking vengeance on human lives. Lilith by the Red Sea Carpet almost entirely covers the floor space, inviting the viewer to experience a multisensorial work closely by circumnavigating the narrow space around it. A central nest-like medallion of tangled water reeds, roses, spices and ceramic elements, indicates a nest of sorts amongst the wreckage, signifying Lilith’s reproductive intent. The plant carpet is wild, a carpet growing its own motifs, sprouting its own source material. Strewn with swathes of fresh herbs, cinnamon quills, rose hips, star anise and hand formed porcelain roses, its powerful aroma is ambiguous, evoking both an Aryuvedic place of well-being, rest and recovery, Lilith’s desert ‘safe space’, and a place of seduction. This multisensorial aspect, inviting the viewer to respond sensually through smell and tactility, is powerfully evocative. The medallion centre is obscured by reeds, requiring the viewer to peer in closely for a glimpse of the large central rose carved in grey unfired clay, encircled by shiny red glazed ceramic eggs. This central space also presents the viewer with the only image of ‘home’ in the triptych, one of chaotic wreckage, blood red eggs, a home assembled inside someone else’s home, a dangerous invasion: Here the interloper in the nest is doing the breeding. Initially Lilith Carpet has a smooth white surface, undulating and cream-cheese-shiny, with a faintly lined texture evoking rows of woven carpet threads, desert sand, sea-bed, tide lines on sand. But this allusion to the Red sea quickly passes: the sticky soft cheese surface attracts insects, dirt, careless-inquisitive footprints, and dries to a dull, cracked, ruptured matt, the porcelain unable to support the life of its central living plant motifs, a carpet slowly extinguishing itself. And over time, the cracks begin to form the faint trace of their own carpet pattern, revealing the porcelain oval slabs cut straight from the bag and laid onto the floor before they were worked together to form a smooth surface, the material reasserting itself to lay bare its making processes.

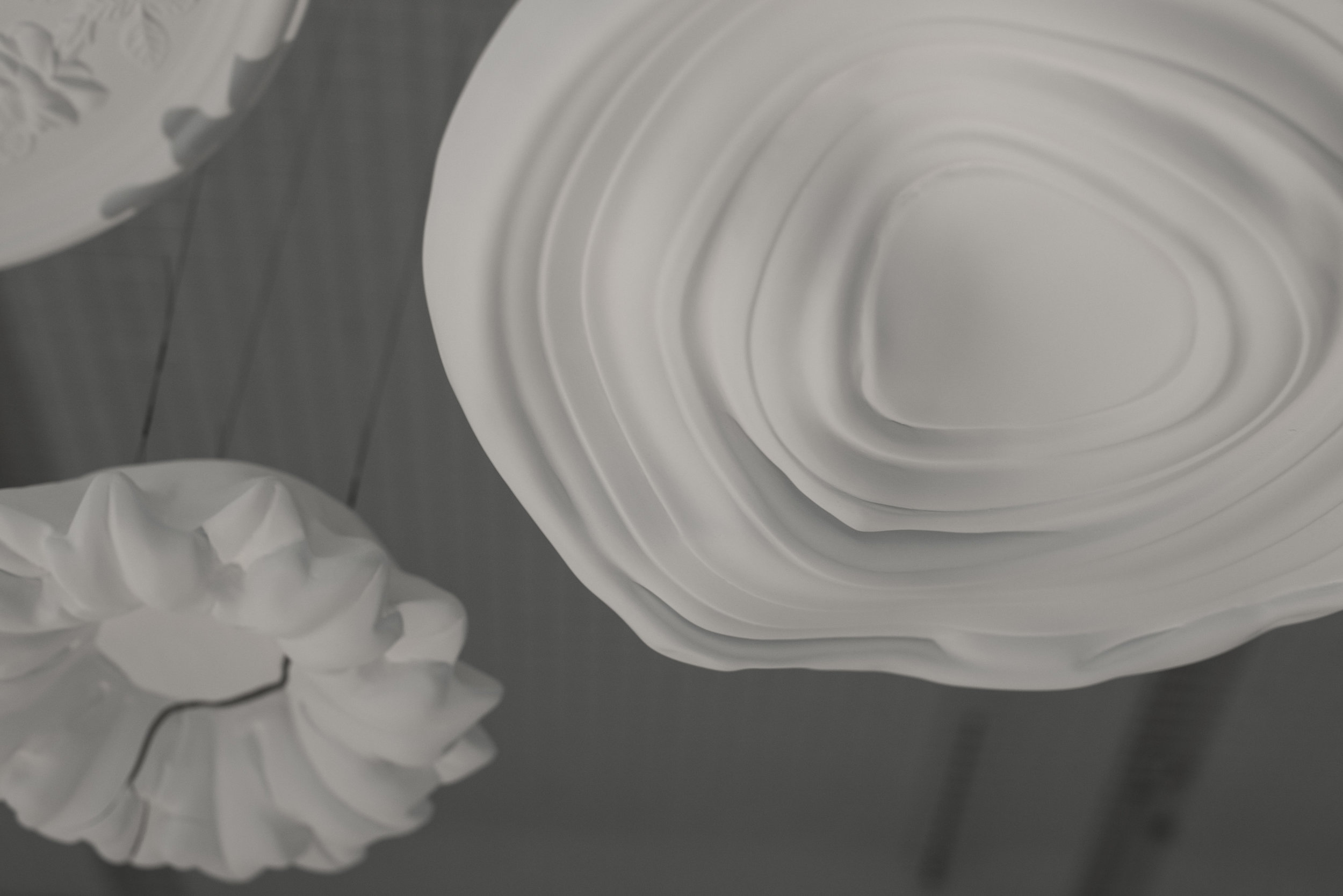

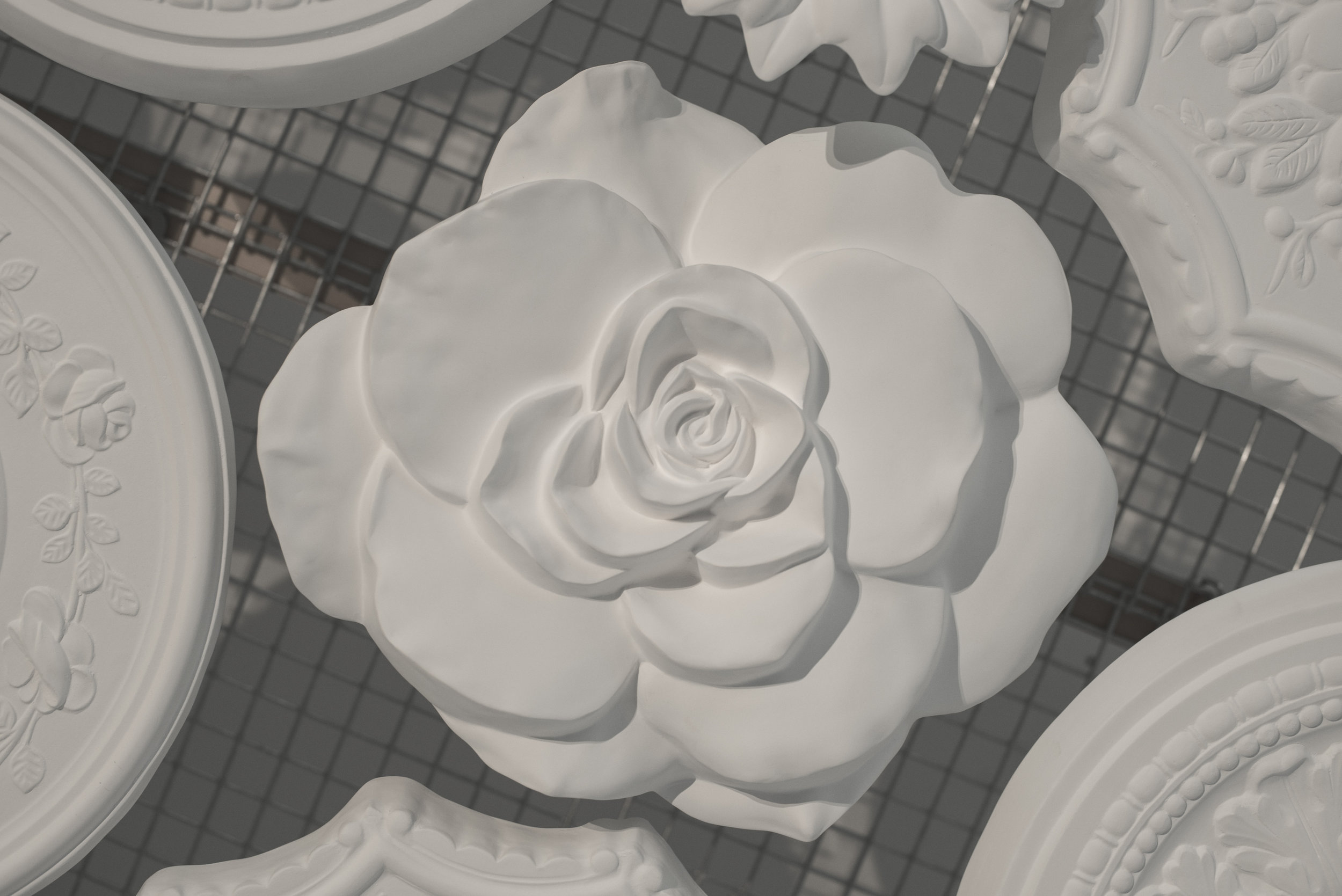

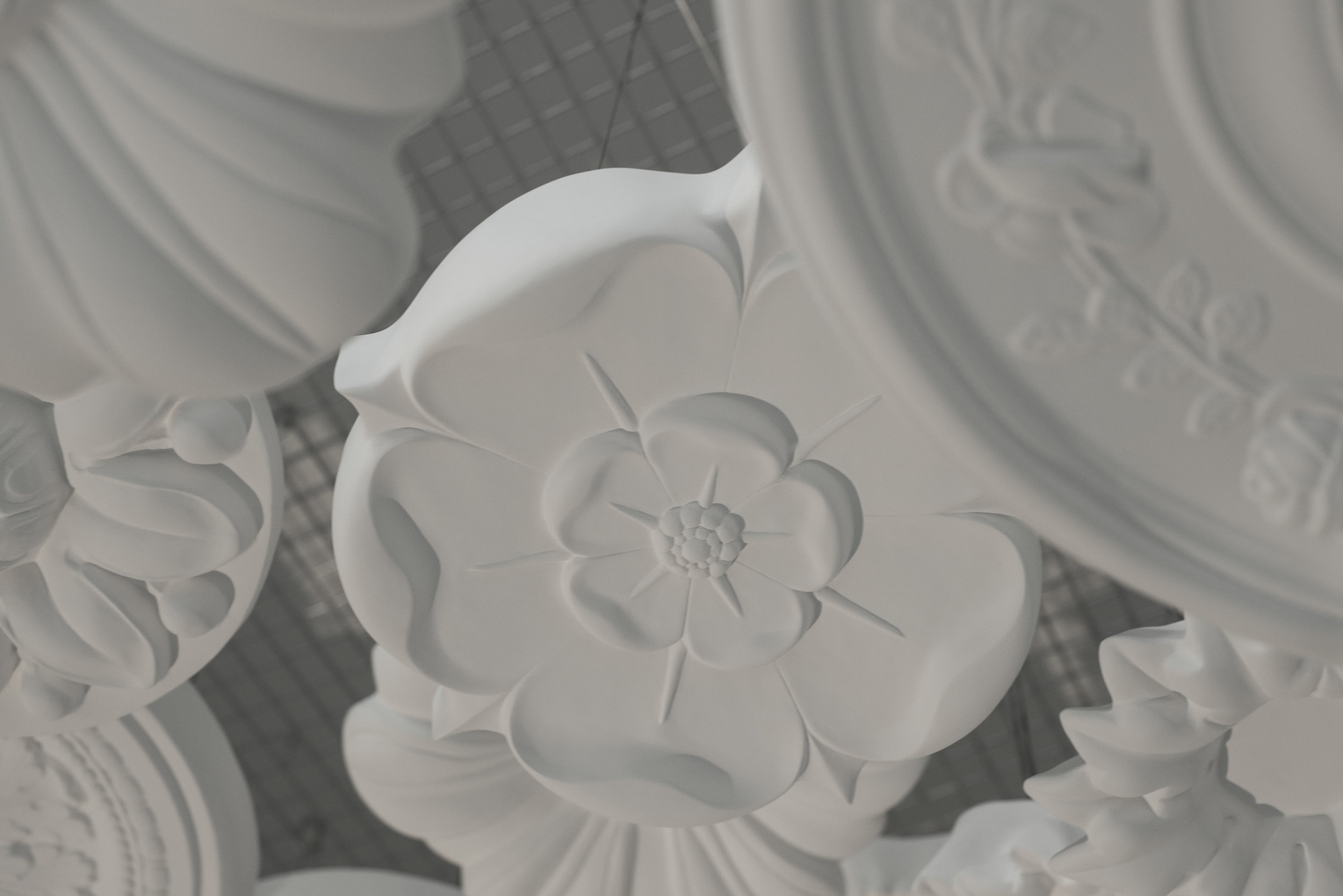

Flock

Flock, December 2021, Private house, Photo: Nedim Nazerali

Photos 1, 3, 5: Michal Goldschmidt; Photos 2, 4, 6 and video clip: Nedim Nazerali

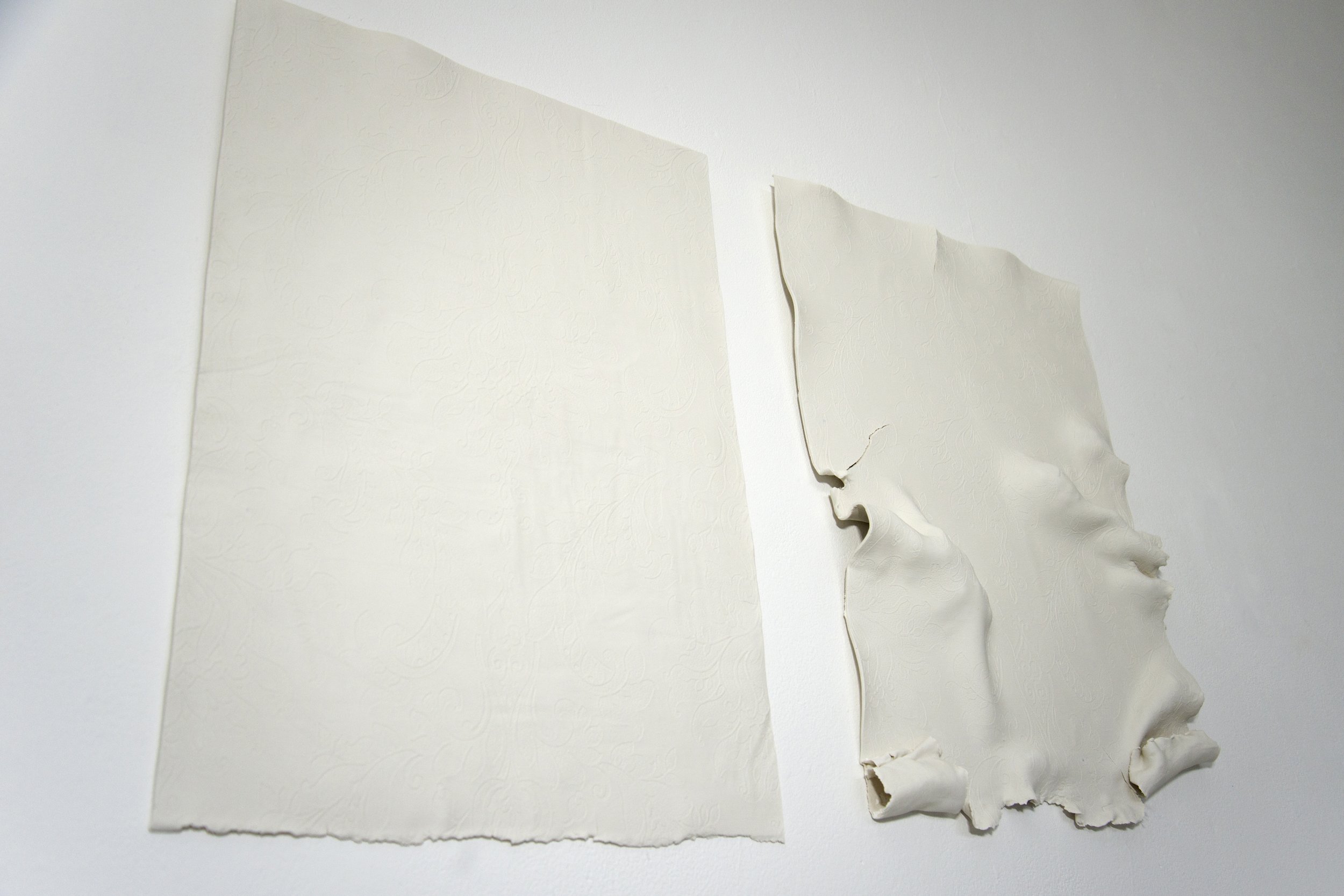

In Flock porcelain wallpaper pieces entirely cover two walls of a small room. Wallpaper appears to be in the process of lifting away from the surface, as if about to take flight, or as if the walls are hovering at the point of implosion. There is a sense of building momentum, that this problematic wallpaper is no longer able to maintain its material and conceptual cover up, that something monumental is bubbling away beneath the surface about to burst forth explosively. The viewer is invited into this disquieting-quieting white space, to stand within a frozen moment of fragmentation. Flock’s title overlays wallpaper and ornithological readings, recalling the plentiful and ambiguous references to birds on the Aramaic bowls. Visually the work suggests the conflation of bird and nest, its walls of wallpaper-plumage enfolding the viewer, evoking the disturbing notion that the materiality of the house itself is live with its wallpaper-plumage. The fabric of the home is not only disturbed but humanized, carrying the weight of emotion: Nippur experiences are bound into this decorative fabric, an intrinsic material part of the home, not just a lingering atmosphere. The pandemic has intensified our relationship to domestic space and brought us close acquaintance with Aramaic bowl problems. Flock’s installation in a small domestic room allows these Late Antique bowl narratives to reside within a private contemporary home. Aramaic bowls were usually found buried under the thresholds and corners of floors in domestic spaces. Flock is installed on two adjacent walls that meet in a corner window, a vulnerable interface between inside and outside worlds, forming the corner of a small room. These walls, in turn, constitute the corner of a house which sits at a corner where two streets meet. One of the walls contains a chimney breast, long covered over with layers of brick, plaster, wallpaper and now with Flock, a truly belt and braces cover-up, that nonetheless has not worked: From these vulnerable points - chimney, window and corner - something has got in and spread outwards across the walls. Above them, deep cracks have appeared in the plaster coving, as if the weight of this overblown symbolism has been too much to materially bear. But the disturbance is also delicate, an exquisite infiltration, porcelain-precious, polite rather than frightening: Flock is seductive and tactile, appealing to the senses - visitors want to touch Flock and reach forward surreptitiously to do so - and this is the sensuality of Lilith.

Early Research

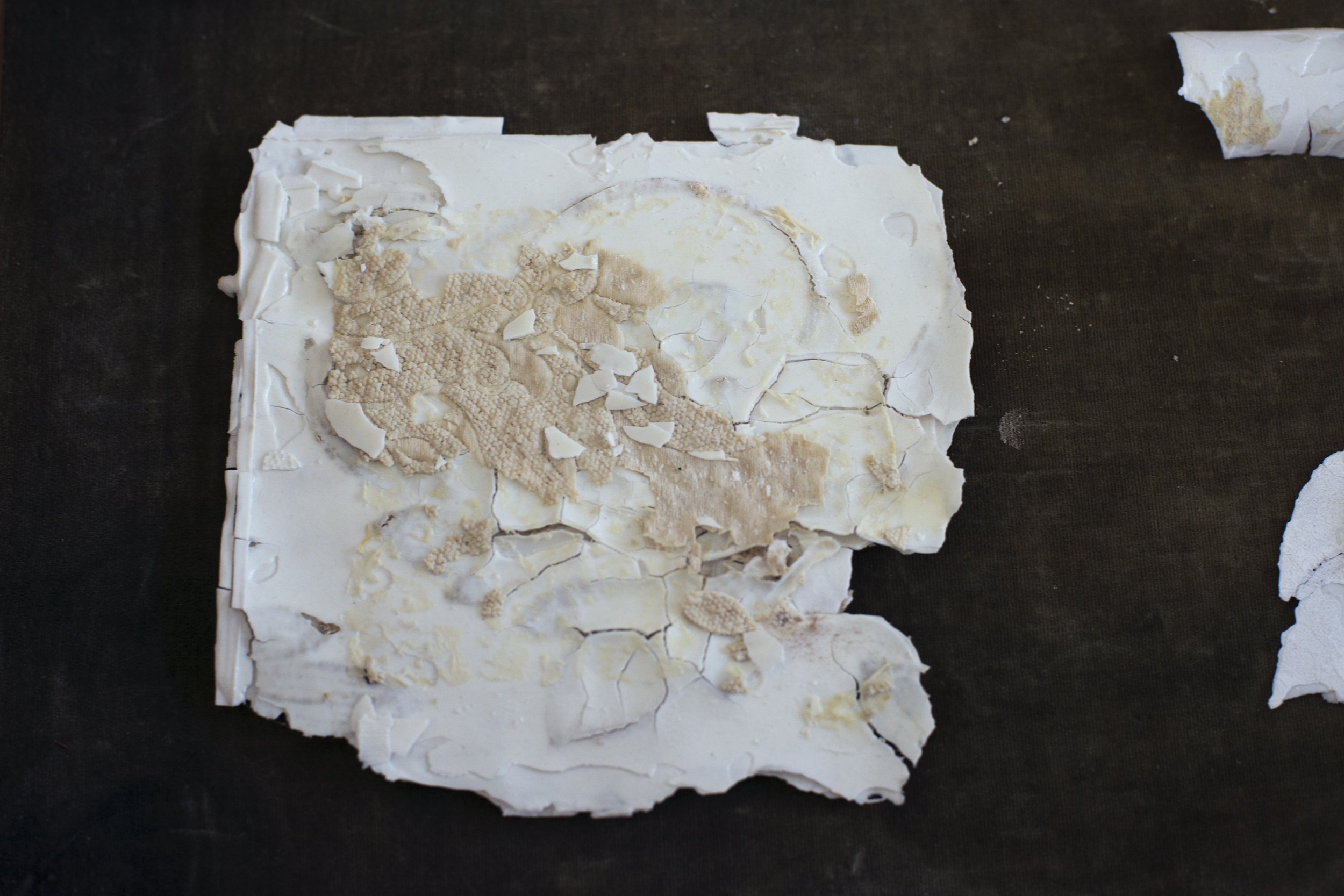

Wallpaper for the Nippur House, June 2014, EKWC

Photos 2-5: Nedim Nazerali

Early research included a seven week residency at EKWC in The Netherlands between May and June 2014. Work there focused on investigations into different ways of working with wallpaper and clay, and the production of specially formulated porcelain in order to make Wallpaper for the Nippur House, a series of six large-scale panels of porcelain wallpaper that evidence distortion and disruption. Back in London, long hours were spent in the university workshops learning how to make plaster slip casting molds. Some of the resulting work was exhibited in “In Process, An Exhibition of Media and Arts Doctoral Research” held between December 2015 and January 2016 at London Gallery West, Project Space and The Forum, University of Westminster.

Hedgerow

Hedgerow is a living plant art work that engages with ecological aesthetics and concerns. It contains multiple indigenous plant species found in UK countryside hedgerows, aiming to be a beautiful and thought provoking ‘life magnet’. Juxtaposing a slice of English countryside onto the urban cityscape, Hedgerow offers food and shelter to an alternative non-human community, as well as oxygen, beauty and amenity to its human visitors, and its placement within a new housing development proposes alternative notions of home. Hedgerow also reaches beyond its site into the community: together with local primary school pupils, we planted two ‘sibling’ hedgerows in their school grounds.